Rubik's Cube Representation

GitHubBackstory

During the first lecture of my Abstract Algebra course, the professor passed out Rubik’s Cubes and explained that the over 43 quintillion states of the cube form a mathematical group. That same semester, I was taking a computer science course called Formal Proof and Verification, which focused on how to use the Lean programming language to prove mathematical statements.

For the final project of the formal proof course, we were asked to pick a topic and code some proofs about it using Lean. I recalled my first day of Abstract Algebra and decided to formalize and verify what I had learned in that first lecture.

I discovered that this had been done before: there was a GitHub repository by Kendall Frey (AKA kendfrey) that formalized the Rubik’s Cube group in Lean 3. I decided to use kendfrey’s code as a reference, and I set out to create my own formalization in Lean 4, taking inspiration from the Lean 3 code and reusing components that I understood and thought were useful.

The Representation

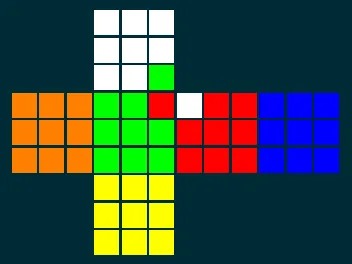

If you are familiar with a Rubik’s Cube, you may already know that the cube is composed of three types of pieces: 6 center pieces, 12 edge pieces, and 8 corner pieces (see Figure 1). Additionally, the center pieces never move relative to each other. No matter how the cube is scrambled, their relative positions are always the same: the yellow, green, and red centers are on adjacent faces (as shown in Figure 1), and the green center is opposite the blue center, and so on.

This is helpful when solving the cube, because we know that, for example, the face with the green center piece will be the green face when the cube is solved. For the purposes of representing the cube, this invariance is useful because it means that the state of the cube is completely determined by the positions of the edge and corner pieces (relative to the center pieces, which we can lock in place and then ignore).

Following kendfrey’s lead, I began representing the cube by representing the state of the edge pieces and the state of the corner pieces separately. The state of the corner pieces can be represented as a combination of two pieces of information: their locations and their rotations, also known as their permutation and their orientation. In other words, given where each corner piece is located and how it is twisted, we know everything there is to know about the state of the corners.

If we label the corner pieces with the numbers 0 through 7, then the locations of the corner pieces can be represented as a permutation of those numbers. Thus, if the cube is solved, the permutation will leave them in order: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. If, on the other hand, the first and second corner pieces were swapped, then the permutation would be 1, 0, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 instead.

We can define default orientations for each corner piece, and then the orientation of each corner piece can be represented as an integer from 0 to 2, where that number represents how many times the corner should be twisted clockwise from its default orientation. These ideas are encoded in the following Lean code:

structure PieceState (pieces orientations: ℕ+) where

permute : Perm (Fin pieces)

orient : Fin pieces → Fin orientations

deriving Repr, DecidableEqIn Lean, Fin represents the set of natural numbers less than a given number, so the permute field of the state is defined to be a permutation of the numbers 0 through 7 in the case that there are 8 pieces. The orient field maps each location to the number of times the piece in that location should be twisted clockwise from its default orientation, so it is a mapping from the set {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7} to the set {0, 1, 2}.

Note that the number of pieces and the number of orientations are both left as inputs to the PieceState structure. This is because the logic used above for corner pieces can be reused for edge pieces, with the only difference being the number of pieces and the number of orientations. We thus have the following definitions:

abbrev CornerType := PieceState 8 3

abbrev EdgeType := PieceState 12 2

abbrev RubiksSuperType := CornerType × EdgeTypeNote that the state of the entire cube is simply defined as a combination of the states of the corner and edge pieces. This is close to the final representation we want, but I named this the RubiksSuperType because it represents a superset of the states of the Rubik’s Cube group. This representation allows for all possible states of the cube that could be achieved by taking the cube apart and putting it back together, but this includes states which one couldn’t achieve with the standard moves of turning the faces of the cube.

The RubiksSuperType includes, for example, states in which a single corner piece is twisted, as shown in Figure 2. This is impossible to arrive at (or solve) by only turning the faces of the cube, as every turn of a face changes the orientation of the four corner pieces on that face symmetrically: the change in orientation of a corner piece is always mirrored by another corner piece on the face being turned, so it is impossible for a single corner to have an orientation of 1 while all others have an orientation of 0. Similarly, it is impossible to achieve a state in which a single edge piece is flipped.

In addition to ensuring the orientation of the pieces is reachable through standard moves, we also need to ensure the permutation of the pieces is reachable through standard moves. While it is possible to achieve any permutation of the corner pieces as well as any permutation of the edge pieces, it is not possible to do so simultaneously. Since every face turn permutes both corners and edges in tandem, the permutations of the corners and edges are linked. This permutation constraint as well as the constraints for orientations are formalized in the following Lean code:

def ValidCube : Set RubiksSuperType := {c |

Perm.sign c.fst.permute = Perm.sign c.snd.permute

∧ Finset.sum (Finset.univ : Finset (Fin 8)) c.fst.orient = 0

∧ Finset.sum (Finset.univ : Finset (Fin 12)) c.snd.orient = 0}To learn more about the justification for these constraints, I recommend this explanatory video.

The Group

Wikipedia defines a group as follows:

In mathematics, a group is a set with an operation that combines any two elements of the set to produce a third element within the same set and the following conditions must hold: the operation is associative, it has an identity element, and every element of the set has an inverse element.

In the case of the Rubik’s Cube group, the set is the set of all possible states of the cube. If we think of each state as being equivalent to a sequence of moves that turn a solved cube into the given state, then the operation for combining two states is to simply chain together the sequences of moves for the two states to produce the resulting state. For example, as shown in Figure 3, we can combine the state representing a single clockwise turn of the green face and the state representing a single clockwise turn of the red face to produce the state representing a single clockwise turn of the green face followed by a single clockwise turn of the red face.

This operation can be naturally extended to states that require several moves, and it can be formalized in Lean as shown here:

def ps_mul {p o : ℕ+} : PieceState p o → PieceState p o → PieceState p o :=

fun a b => {

permute := b.permute * a.permute

orient := (a.orient ∘ b.permute.invFun) + b.orient

}Note that this is defined for PieceStates. We are continuing to use the strategy of creating a formalization that generalizes for both corners and edges and then combining two copies of it to represent the entire cube. To prove that the corner pieces and edge pieces each form groups with this operation, I had to prove that they satisfy the conditions laid out in the definition above. For instance, I defined a function for computing the inverse of a PieceState and then proved that the composition of the inverse and the original state is the identity state (the solved state):

def ps_inv {p o : ℕ+} : PieceState p o → PieceState p o :=

fun ps =>

{ permute := ps.permute⁻¹

orient := (-ps.orient) ∘ ps.permute }

lemma ps_mul_left_inv {p o : ℕ+} : ∀ (a : PieceState p o), ps_mul (ps_inv a) a = {permute := 1, orient := 0} := by

intro a

simp [ps_inv, ps_mul, Function.comp.assoc]After proving that the other conditions held, I could formalize the group structure for PieceStates. This directly generalizes to the group structure for the entire cube, as shown here:

instance PieceGroup (pieces orientations: ℕ+) :

Group (PieceState pieces orientations) := {

mul := ps_mul

mul_assoc := ps_mul_assoc

one := {permute := 1, orient := 0}

one_mul := ps_one_mul

mul_one := ps_mul_one

inv := ps_inv

mul_left_inv := ps_mul_left_inv

}

instance RubiksSuperGroup : Group RubiksSuperType := Prod.instGroupOf course, this is for the overgeneralized RubiksSuperType, so we need to restrict it to the valid states of the cube. This required proving a few more lemmas, but the final result is shown here:

instance RubiksGroup : Subgroup RubiksSuperType := {

carrier := ValidCube

mul_mem' := mul_mem'

one_mem' := one_mem'

inv_mem' := inv_mem'

}And there you have it: the Rubik’s Cube group! It’s validity is not only proven rigorously in unambiguous Lean code, but also verified by a computer.

In addition to the formalization of the Rubik’s Cube group, I also created a few other proofs and structures. For instance, I verified that a single twisted corner cannot be achieved by any sequence of standard moves, and I formalized a solution strategy that generates a sequence of moves that will solve the cube from any (valid) state. For more details, please see the GitHub repository for the project.